Wrights Hill Gun Emplacement

-

The construction of 9.2-inch gun batteries to protect New Zealand’s major ports was first approved by the army in 1934. Government approval finally came in 1939 but delays in production meant that work on the fortresses did not begin in earnest until late 1942. Three of these fortresses were built, on Whangaparaoa Peninsula, Waiheke Island – to defend Auckland – and Wrights Hill, to defend Wellington. A further fortress was planned at Lyttelton but was never built. The Wrights Hill 9.2-inch Mk XV guns on Mk IX mountings were not completely installed until after the end of the war and even then only two of the planned three guns were emplaced. The third gun at each fortress was cancelled after the fortunes of the war in the Pacific turned in the Allies’ favour. The Wrights Hill Fortress was not completed until after the war; the two guns were finally test-fired in 1946 and 1947 and then never fired again. In the post-war period Wrights Hill was intended to be used as a training facility but in the end this hardly occurred and only basic maintenance was undertaken. It was abandoned by the Army in 1957. In 1960 the guns were scrapped, along with many of the interior fittings of the fortress.

Apart from partial use by Post Office telecommunications staff, the fort lay closed up and dormant until 1989 when it was opened up for public viewing by the Karori Lions Club. Since 1992, the fortress has been steadily restored and regularly opened for the public by the Wrights Hill Fortress Restoration Society.

The 9.2-inch batteries were the biggest land based defensive batteries ever erected in New Zealand. They were capable of outranging the guns of those enemy ships seen as most likely to make raids on New Zealand cities and ports, and had a range beyond the visual horizon. Although only two of the emplacements were completed to any extent technically, upon the test-firing of the guns Wrights Hill was capable of being used as a battery for its intended purpose.

Collectively, the 9.2-inch coastal defence batteries were a hugely expensive and demanding military enterprise, but one that ultimately had only a very brief history of use, and no use – fortuitiously – for its intended purpose.

-

close

Physical Description

-

Setting

close

Wrights Hill Fortress is located on top of the eponymous hill, a steep, high and somewhat isolated landform to the north-east side of Karori, standing apart from the typical long ridgelines of this part of Wellington. From this elevated (and very exposed) position, there are long views all around. At some 300m above sea level, the fortress had a commanding firing position over Cook Strait and the Tasman Sea, with a visual horizon of over 60km. The hill is reserve land, today covered with slowly regenerating native bush.

-

Streetscape or Landscape

close

The Wrights Hill Fortress comprises an amalgam of key elements distributed around the top of the hill, including the gun emplacements, the extensive underground complex – of magazines, engine rooms, workshops etc., war shelters, observation posts, and supporting infrastructure and roads. By far the greatest part of the Fortress lies underground; by design the above-ground parts were discretely located and camouflaged or otherwise made difficult to see.

The surviving structures are all made of reinforced concrete, with the distinctive raw off-form finish of the time. The design of each structure is uncompromisingly utilitarian and brutal – all parts were made to be fit for their purpose. Although no concession was made for attractiveness of appearance, the structures have a rugged and uncompromising aesthetic that is strongly characteristic of their time.

-

Contents and Extent

close

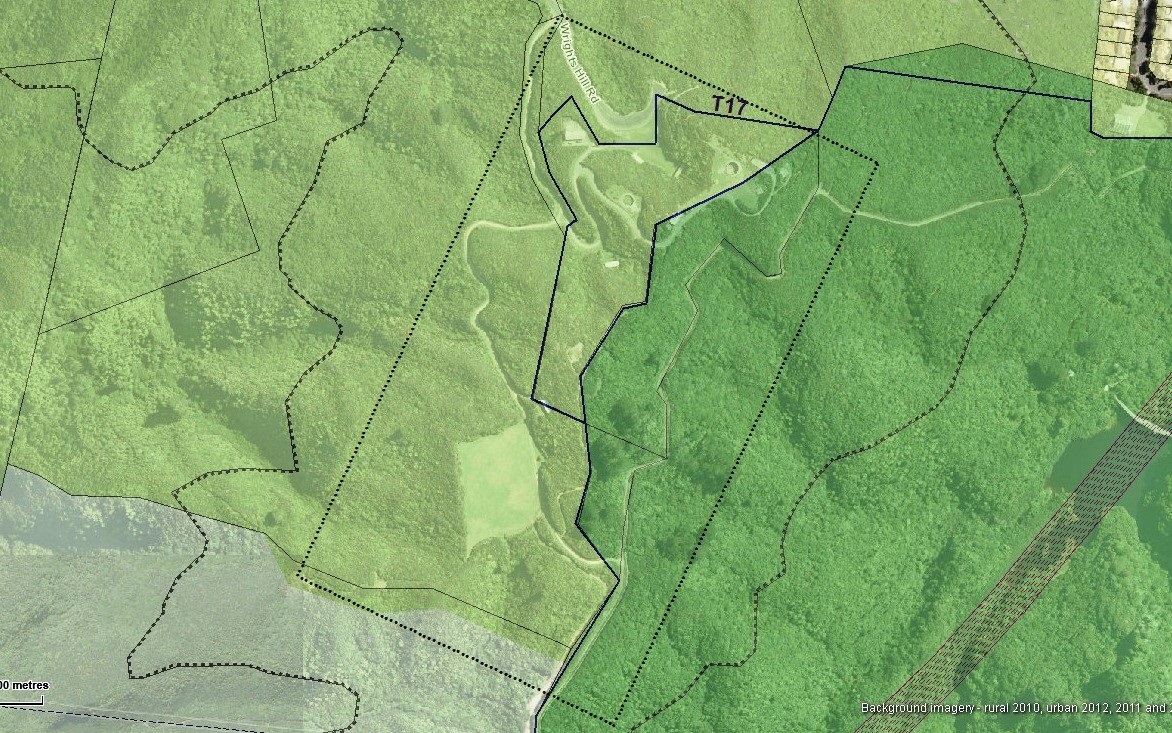

Wrights Hill Heritage Area occupies an area on the top of the hill that bears its name. The heritage area is defined by a rectangle that incorporates (in part or full) Sections 13, 14, 15, 16 and 17 Upper Kaiwharawhara District, and Lot 1, DP 313319. Much of the area is also a recreation reserve under the Reserves Act 1977. The great majority of the complex is underground, the extent of which is marked on the surface (approximately) by the four war shelters. On the surface, apart from the war shelters, there are three gun pits, the fresh air intake building, observation post, two exhaust shaft vents, the miniature range ruins and the parade ground, and various additions to existing building.

-

Buildings

close

Not available

-

Structures and Features

close

The Wrights Hill Fortress comprises an amalgam of key elements distributed around the top of the hill, including the gun emplacements, the extensive underground complex – of magazines, engine rooms, workshops etc., war shelters, observation posts, and supporting infrastructure and roads. By far the greatest part of the Fortress lies underground; by design the above-ground parts were discretely located and camouflaged or otherwise made difficult to see.

The surviving structures are all made of reinforced concrete, with the distinctive raw off-form finish of the time. The design of each structure is uncompromisingly utilitarian and brutal – all parts were made to be fit for their purpose. Although no concession was made for attractiveness of appearance, the structures have a rugged and uncompromising aesthetic that is strongly characteristic of their time.

Gun emplacements

The gun emplacements (now reduced to empty pits) were built at intervals across the top of the hill running roughly north-south. No. 1 emplacement was the most northerly. No. 3 was some distance from the others. They were situated and oriented to cover not only Cook Strait but the sea to the west of Wellington.

As a result of scrapping of the guns, gun houses (turrets) and mountings in c. 1960-61, today little remains of the emplacements beyond the reinforced concrete shells and the apron. Access to the underground tunnel complex from the gun emplacements was sealed off in 1960.

The emplacements, excavated into the ground, are very large circular structures built of heavy reinforced concrete. Each gun pit is 12.5 metres in diameter with a maximum depth of 3.5 metres. The mounting bolts for the guns form a large circle in the centre of the pit; beyond this a concrete platform runs about half-way around the circle (the balance of the circle was originally made up with a steel platform). The gun mounting is circumscribed with rails used by the shell trolley, used to bring the shells from the shell hoist to the loading mechanism at the gun. Beyond this, there are shell store recesses (now without doors) around the perimeter of the pit. A sealed-up opening covers the passage into the underground complex and the access to the shell hoist. Only one gun pit, No. 1, is fully excavated and it has a timber balustrade around it for health and safety reasons. No. 2 is half excavated, while No. 3 is still filled to the rim.

Underground complex

The 9.2-inch battery has a vast underground complex that provided all the supporting functions for the guns, all linked together by an extensive network of distinctive horse-shoe shaped tunnels (the tunnel profile was borrowed from New Zealand Rail), stairs and passages. The main spaces include:

- Magazines

- Workshops

- Engine rooms

- Generator rooms associated with each gun pit

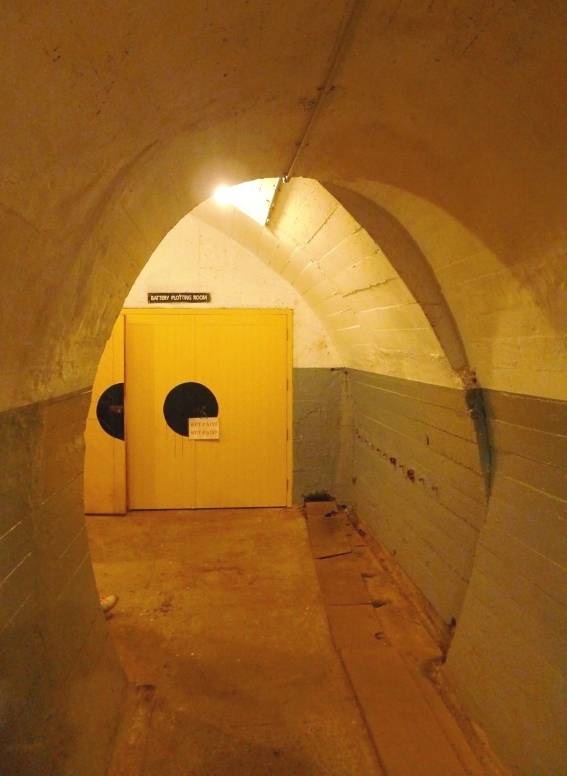

- Fortress plotting room

- Battery plotting room

- Fuel store

The major spaces are all vaulted, formed using an unusual flattened ellipsoidal-profile arch, also derived from the standard railway tunnel profile used at Tawa Flat, and lined with concrete. The form of the smaller tunnels for passages and stairs was taken from the standard railway access tunnel. The tunnels cover a total distance of 610 metres and there are 127 metres of stairways.

Many of the key features of the complex were replicated at each gun emplacement. From the gun emplacement itself, the first flight of stairs down joins a long stair – which leads down to the magazines level – and a short flight up to the pump chamber, which is set just off to the side of and underneath the emplacement. The pump chamber contained the hydraulic pumps and auxiliary engines needed to drive the gun mountings. The stair joins at the bottom into a passage leading to the magazine (cartridge and shell stores), which lie under the other side of the emplacement. These were built within a large vaulted chamber; the shell store was constructed as a small brick building, with a timber-framed roof, that sat inside the magazine walls. The magazine is linked directly to the emplacement by a shell hoist.

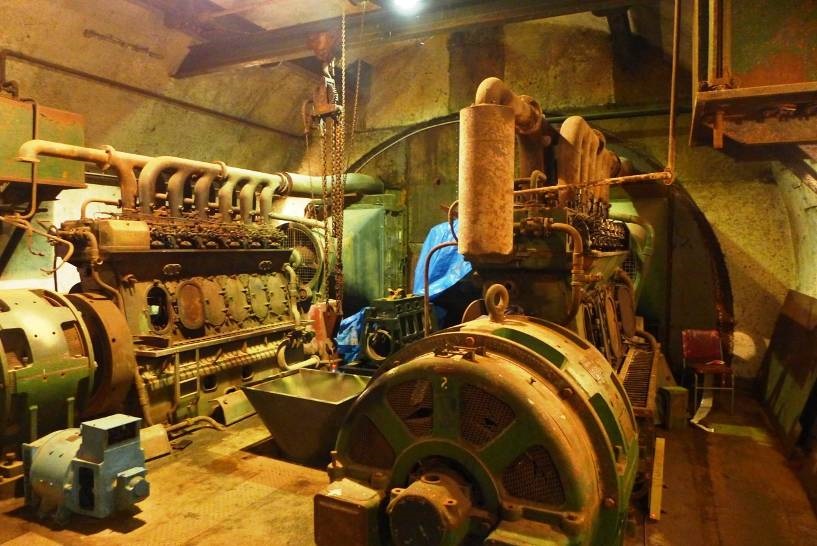

The main passage links the three gun emplacements, via an array of stairs and passages. Several key spaces branch off the main passage halfway between the Nos. 2 and 3 guns. These include the battery plotting room, fortress plotting room and command post. The oil store and engine room are located between the Nos. 1 and 2 guns. The engine room is perhaps the most visually dramatic of the service spaces, as it retains a significant amount of its original equipment, albeit much reduced from its configuration at the end of the war. Surviving equipment includes one of the two diesel engines, a diesel generator, remnant electrical switchgear, the steel baffle to the exhaust chamber, pumps and other equipment. Beyond the baffle is a y-shaped pair of exhaust tunnels which lead horizontally from the baffle area to the vertical exhaust shafts. There is also a separate air intake shaft, at the opposite end to the exhaust. In fact, the retention of this equipment is one of the defining characteristics of Wrights Hill, setting it aside from the other two batteries in Auckland.

Services – power, water and hydraulic lines – which were provided throughout, along with the ‘magslip’ communication wiring (for fire direction and control for the guns), have largely been removed over time.

War shelters / observation post

There are four war shelters, provided as a place of retreat for staff in the event of attack. There was one shelter provided for each gun and built against the hillside at each of the tunnel portals, unlike the arrangement at, for instance, Whangaparaoa, where the shelters are separated from the tunnel portals and access is solely external. A fourth shelter was provided for staff in the plotting rooms. There is also an observation post to the north-east of No. 1 gun.

The shelters are all long single-storey rectangular buildings constructed in reinforced concrete, with flat roofs, to the same general pattern. Apart from the shelter at the main entrance – war shelter 1, which had three entrances – they had two sets of entrance doors, one single and one double. Originally the war shelters were designed with no windows and two were built that way. When it was discovered, in the course of construction, that ventilation was quite inadequate without some sort of aperture, windows were cut in the two shelters already built and provided in the two shelters still to be built. Over the main entrance to each was a substantial porch with sides. Significant restoration work has been undertaken on some of the internal spaces.

The observation post has an adjoining radio room and separate outside entrances, double steel doors leading from the observation post and one single steel door from the radio room. The main viewing slot extends around two of the exterior walls of the structure and once offered a view over Wellington that extended from about where the location of the Brooklyn turbine to the Hutt Valley. There was also a window looking north-east. These views have since been reduced by regenerating bush. Alongside the radio room was a small engine room. The Post and Telegraph Department built an addition to the building c.1957, which still stands.

Miniature Range building and parade ground

Originally two storeys high, with a timber framed second storey, the Miniature Range building has been reduced to a one-storey concrete shell, pockmarked with gun shot damage. It sits on the edge of an open area originally intended as a parade ground for battery personnel.

-

Other Features

close

Not available

-

Setting

close

-

close

Historic Context

-

The first efforts to defend Wellington from external attack involved the construction of a series of fortifications around the harbour to respond to the ‘Russian Scare’ of the 1880s. Work began on temporary fortifications in 1885 and permanent construction began the following year. The main fortification was Fort Ballance, on the Miramar Peninsula, but there were other batteries built at key locations around the harbour. By 1898 Wellington had seven separate fortifications: Forts Ballance, Buckley, Gordon and Kelburne and batteries at the Botanic Gardens, Point Halswell and Kau Point.

By the early 1900s many of these batteries became obsolete, mainly due to changes in armament technology. A new battery to mount a modern armament, the 6-inch Mk VII, was planned on Dorset Point. Fort Dorset, as it became known, also incorporated a battery camp and searchlight emplacements. The battery’s capacity was extended to two guns and the battery was completed by early 1910. Wellington’s coastal defences were not called upon during World War I and in the aftermath of the war defence was a low priority for successive governments.

The lack of investment in the country’s military capability was exacerbated by the Depression, which left government coffers dry. By the time the government committed itself to modernising the armed forces in the 1930s, tensions were rising in Europe. In 1933, Major-General Sinclair-Burgess, head of the New Zealand Army, proposed a six year modernisation programme that was approved by the Government. It involved a construction outlay of £840,000, of which £309,200 was to be used for the building of new coast defence batteries at Wellington and Auckland.

Advances in range finding technology now enabled big guns to engage targets accurately at their ballistic maximum range, which was far beyond the visual horizon of the guns themselves. To enable the guns to actually hit a target a substantial battery infrastructure was required. In particular, widely-spaced observation posts were required forward of the battery positions to track targets and observe the fall of shot. The War Office in England, in recommending batteries to defend the ports of Wellington and Auckland, argued for 9.2-inch batteries, which with the considerably greater range of the larger guns could defend much more water than smaller guns. The building of 9.2-inch batteries was approved by the army in 1934. Amongst other potential battery locations, the site in Wellington, on top of Wrights Hill, was identified at this time. However, the anticipated cost was considerable and the government opted instead for two 6-inch batteries at Auckland and Wellington. One of these was at Palmer Head, on the Miramar Peninsula. This battery was completed in 1939, with two guns emplaced (a third gun was added in 1942). These were the country’s first counter-bombardment or ‘fortress system’ batteries.

The Army continued to plan for 9.2-inch batteries and in 1937 a five-year work programme was presented to Cabinet that included the construction of a 9.2-inch battery at Wellington.This time the work was approved, although it was then immediately delayed, again on the grounds of cost.

With the outbreak of war in Europe in 1939, the Government immediately approved the 9.2-inch coastal defence batteries, but work was not able to proceed because British manufacturers could not say when they would be able to deliver the guns. However, construction of the 9.2-inch batteries for Wellington and Auckland, where a second battery was added to the programme, as well as Lyttelton, now became a matter of priority. In March 1942, British manufacturers finally were able to advise delivery dates of within 12 months for the first two guns for the Wellington and Auckland batteries, with the third to follow later.Construction of the batteries proceeded with maximum urgency.

A reconnaissance of Wrights Hill was carried out in April 1942. The main value of the location was its elevation, at more than 300 metres above sea level, giving a visual horizon of around 60km. Despite the occasionally extreme weather conditions encountered it was regarded as an ideal site. The hill, once bush-clad but by this time more or less bare land, was still being farmed when the army purchased it for the battery.

The Army and Public Works Department sent personnel to Sydney, Australia, to inspect the recently completed 9.2-inch batteries at North Head and Cape Banks. They returned with copies of the Australian plans which were complemented by a full set of constructional drawings sent from the War Office in the United Kingdom. These included drawings for emplacements, pump chambers, magazines, engine and plotting rooms.

War time introduced a number of problems for the construction, including a critically short supply of steel, a lack of skilled workers, and the sheer time that reinforced concrete construction would take. Alternatives to the traditional ‘cut and cover’ approach, where the battery was dug out and then roofed with a heavy concrete burster slab, had to be considered for the construction of the new gun batteries. It was calculated that tunnelling at a point 12 metres below the surface would offer the equivalent ballistic protection to a burster slab. So, this approach was taken to create, firstly, the plotting rooms at Motutapu Island (1940-42), and then many other underground tunnels and chambers, including all of those associated with the three 9.2-inch batteries. There were other benefits to this approach. The connecting tunnels provided a safe and easy access for cable runs, communication equipment and personnel, and, the battery was relatively easily and effectively camouflaged from the air, as only the emplacements needed to be excavated, and the entrances to the tunnel network could be located some distance from the battery complex.

Each 9.2-inch installation had a military code; Wrights Hill was ‘W’. A special section of the Public Works Department was formed to prepare the detailed working drawings and designs. To save time, each battery used the same design for emplacements, tunnels and underground chambers. However, differing topography and artillery requirements meant that the overall battery layouts had to be different in each case. Wrights Hill was the most compact and Waiheke the most dispersed.

Once the local topographical plan for each battery was prepared, a detailed contour plan of each site was made. A dispersal policy dictated that emplacements should be sited approximately 180 metres apart. When the tunnel locations had been finalised, the designers looked at existing tunnel forms that could be speedily adapted to provide the dimensions of the main chambers. For this they chose an adaptation of the semi-circular tunnel design adopted for the Tawa Flat railway deviation, completed in 1936.It was chosen mainly because it had proved a functional design and there was already considerable experience in its execution.

The tunnelling was initiated by the PWD, which was long familiar with building tunnels for rail and road projects and had over 70 years of experience of infrastructure construction all over the country. New Zealand’s rock, particularly the common greywacke, was not difficult to drive and there were experienced tunnellers in the country, working for both the PWD and for private companies. The 9.2-inch battery intended to be built at Wrights Hill was the standard British War Office design and similar to the recently constructed 6-inch batteries; the complex included magazines, engine and plotting rooms and observation posts. The main difference from the 6-inch batteries arose from the need for power to elevate the gun carriage and traverse the 9.2-inch turret, which weighed 142 tons, so new chambers adjacent to the emplacements had to be planned to accommodate the electric motors and hydraulic pumps necessary to move the guns. The main engine room needed to be located in a central position relative to the guns, and would be at least twice the size of its predecessors. Each emplacement was conservatively planned to be two and a half times the size of a 6-inch.

The construction camp for 160 men was established in September 1942 at the end of Campbell Street, some distance from the work site. The road was extended from there up to the battery area, a sharp climb of 180 metres over a distance of nearly 2.5 kilometres. Its construction was a considerable challenge in itself.

Due to the urgency of the project, construction at the three battery sites often proceeded simultaneously with the preparation of working drawings. As work got underway it became evident that the Public Works Department did not have sufficient resources to build all the batteries simultaneously. At Wrights Hill most of the major work was taken on by a private company, Downer & Co. Ltd. A major problem was the shortage of plant and machinery and there were serious problems in keeping machinery running, not helped by wartime difficulties in procuring replacement parts from overseas. Despite this, tunnelling was underway by December 1942.

The first work undertaken was the excavation of the main adits or drives. This was followed by excavation of the main chambers. To improve access to these main chambers, temporary drives were also excavated. While construction was progressing there was a major redesign of the battery complex.Originally the only access to the gun pits was to be provided by the munition lifts in the magazines, but it was also decided to provide stair access. Several right angled turns in the access tunnels near the entrances were also added; it was thought that without this precaution the blast from firing the guns would reverberate through the tunnels and cause damage to machinery and instruments installed in the chambers.

While digging proceeded, concreting began. It was produced entirely on site using three large mixers which could make up to 100 cubic metres of concrete in an eight hour period.In December 1943, with Downer and Co. running short of men and equipment, the Public Works Department stepped in to help the contractors.The firmness of the greywacke meant that concreting of the tunnels and chambers could proceed without shoring, which undoubtedly quickened construction. However, shortages of timber for boxing nearly brought work to a halt at times.Concrete walls were nearly all a uniform 250mm thick with reinforcing only required at end walls. After the initial concreting had been poured it was found that the planned drains were inadequate to cope with water seepage. The floor areas had to be reopened and enlarged drains installed. In all, at Wrights Hill, approximately 9,333 cubic metres of material was excavated and 2,900 cubic metres of concrete poured underground.

When the tunnelling and concreting was sufficiently advanced, a start was made on the excavation of the three gun emplacements. Construction entailed the excavation of a pit 15 metres in diameter and 4.5 metres deep. This was done by the Public Works Department, with the concreting work completed by private contractor. Each of these massive structures required about 760 cubic metres of concrete. Most of the concrete went into the foundation block, a reinforced slab some 1.8 metres deep. The pit was a circular structure with shell recesses built into the perimeter. Off to one side of the emplacement was constructed a small chamber which housed the electric motors, water and oil storage tanks and pumps required to power the gun mounting. Off this pump chamber ran a passageway connecting the pump chamber to the emplacement and the stairs to the tunnel complex below. There was a vertical concrete shaft linking the emplacement with the magazine below which was occupied by the powered munitions hoist used to supply shell and cartridge to the gun.

By the end of 1943, all excavations had been completed and concreting of the tunnels, chambers and emplacements was well advanced. From the commencement of the 9.2-inch programme it had received absolute priority of allocation of workers and resources in the New Zealand heavy construction industry. However, by late 1943 the strategic course of the war in the Pacific had significantly changed in the Allies’ favour and many of the workers were thereafter transferred to hydro-electric development on the Waikato River, including the building of four power stations.

Despite this change in circumstances, work continued at the batteries, using men from two construction units recently returned to New Zealand from the 3rd Division in the Pacific. At Wrights Hill the civil engineering part of the project was essentially complete by June 1944. Small Public Works Department teams remained at each site to do essential maintenance and assist the Army parties that had begun to install the guns and equipment.

At this stage it became apparent that the batteries would be most unikely to serve in an operational role. The Government, conscious of the great expense of the 9.2-inch battery project, looked at ways of reducing costs. The battery at Lyttelton had already been cancelled outright before construction began but the Government wanted more savings to be found. It eventually managed to get the Army to agree that the two guns and the equipment already delivered for each of the three batteries would be sufficient to complete them to a minimal standard. The third gun and other equipment for each battery yet to be delivered would be deferred until after the end of the war and purchased at a later date. The Army was reluctant to agree to this but finally had little choice when the British manufacturers advised that there would be further delays in production due to an alteration in production rates.

There was still considerable opinion in favour of eventually emplacing all three guns at each battery. The principal benefits were the opportunity three guns gave to cover a broader area around a target with fire (bracketing), and to counter evasive action by a target ship. The General Officer Commanding New Zealand Military Forces however conceded that ‘dates of supply are so distant to raise questions whether the orders should not be cancelled....I consider that two gun batteries would be a sufficient safeguard for the batteries in New Zealand.’ This was all the Government needed to hear and on 29 January 1944 the Minister of Defence recommended to the War Cabinet, that ‘approval be given to the cancellation of the third gun of each of the 9.2-inch batteries...together with such associated stores and equipment which it is possible to cancel.’It was estimated that the cancelling of the third guns would save the New Zealand Government £150,000.

Supporting this key decision, there was a general reduction in all other associated projects relating to the batteries. The extensive network of observation posts for the batteries was severely curtailed. Of Wrights Hill’s observation posts only that at Mt Albert (Island Bay) and Cape Terawhiti were completed; the others (Opau, Pipanui and North Head) were either suspended or cancelled. It was becoming clear that radar, the new and highly effective system of position fixing, would do this work in the future, rather than visual observations. However, this meant that the whole fortress system of rangefinding, the basis on which 9.2-inch batteries were designed, would not be of any use for training purposes, the primary intended post-war purpose of the battery. Barracks were planned to be built next to the battery, but were also cancelled. The Army had to make do with the Public Works camp in Campbell Street.

At this stage it was also decided that Wrights Hill would be completed to a minimal operational standard and thereafter used for training. The only firing that had to take place would be the acceptance rounds to check the two guns had been correctly installed. Whangaparaoa was also to be completed to a similar standard, and used for training, but it was also to be used for practice firing from time to time. Waiheke was completed to a standard sufficient just to ensure preservation of the ordnance and equipment delivered to the site, pending a later decision on its future.

Army installation parties took over the battery sites in 1944 and, with limited Public Works assistance, began the process of completing the batteries. The installation of power - hydraulic and electric, including magslip communication cabling, and all associated structures - occupied an installation party, led by Captain F.L. Mason, just over two years from March 1944.

The two guns and associated mounts and components arrived from Britain by ship early in 1944; they were unloaded on to a barge then taken on to the Wellington docks. They were transported to Karori via Glenmore St and up the unsealed Wrights Hill Rd. The first components for No. 1 gun were moved from the docks on 11 April 1944 and this work was completed in one week. The biggest gun component was the barrel. That alone weighed 28 tonnes and had to be hauled up Wrights Hill Rd behind a huge D8 tractor. One barrel got caught on a corner and took two hours to be freed.

The huge guns took a considerable time to be installed. Installation was carried out by two groups of army personnel, one for the guns and the other for power. With the exception of the overhead shield, No. 1 gun was completed by 1 August 1944. Only then did work on No. 2 gun begin.However it was not until 28 June 1946 that No. 1 gun was fired for the first and only time.

Prior to construction, it was thought that the battery’s elevation and situation near the top of the hill would make the installation of porous drains behind the tunnel linings unnecessary. However, in winter, after concreting had been completed, large amounts of water began to seep through the tunnel linings. This was partially corrected by chasing the construction joints and leading these to the underfloor drainage system, but this did not fully solve the problem, and condensation sometimes lingered for days in the complex. After exhaustive testing the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research suggested construction of a reinforced concrete tower, containing fans and filters, over the air intake for ventilation purposes. This largely solved the problem. This building survives today. Also, to control underground temperatures, heaters were installed near the magazines, plotting room and pump chambers.

In addition to the actual operation of the battery, a miniature range building was constructed near the battery for training. In this two-storey building, officers would practice engagements by observing model ships moving on a large map of the sea area around the battery. Through simulated rangefinding equipment, they would pass instructions onto the plotting rooms which would pass bearings onto the guns. Firing would be simulated, and a device in the range would calculate fall of shot on the map.

Wrights Hill was never fully manned. As with all the 9.2-inch batteries it was a very large military installation, and would have required over 250 personnel to keep it fully operational. As the war came to an end, it was clear the batteries would have little future use. Wrights Hill was only used briefly for training purposes. Whangaparaoa was also used for training and also hosted Coast Artillery Annual Camps. Waiheke was eventually the home of just a caretaker and his wife.

On June 28 1946 the No. 1 gun at Wrights Hill fired three acceptance rounds, at different bearings and ranges, into Cook Strait. No. 2 gun was fired on March 26 1947.On both occasions the citizens of Wellington were warned of the impending firing. On both occasions, the residents of Karori were surprised by how loud the report was. In the earlier test several house windows were blown out. After the 1947 proofing there were reports of damage from throughout the fortress; ‘inexplicable’ according to the Commander of the 10th Coast Regiment, considering that there was little damage underground during the 1946 firing. One porch next to a war shelter was completely destroyed and windows blown out of the shelters while, inside, the pinex lifted off in many places in the plotting rooms. For all that, both tests were considered highly successful, despite gloomy weather on both days making observation of the fall of shot very difficult.

After the guns’ acceptance rounds army teams and tradesmen continued installation work at Wrights Hill as far as was practicable. This work ceased in 1949 and Wrights Hill was put to a ‘care and maintenance’ status. Effectively this meant that very little was done beyond security and very basic maintenance (the engines were run monthly). By 1952 the Army acknowledged that due to a shortage of staff the condition of Wrights Hill fortress had deteriorated to the point that considerable work was required before it could be returned to the state it was in four years previous.

The battery construction camp continued to be used after the war. After installation teams left, the camp was occupied in 1947 by workers of the State Hydro Electric Department who were building the Khandallah-Central Park transmission line. They left the camp in December 1949. The camp was finally dismantled and removed about 1954.

In 1953, management of the Wrights Hill battery was placed on a ‘long term care and maintenance basis’.All ammunition and stores and equipment likely to deteriorate were removed from the fortress and the complex was sealed up in a state of preservation. Steel shutters were fitted around the windows of the war shelters to prevent the weekly ‘smashing of doors, breaking of electrical fitting and interfering with equipment.’ Despite this, with the fortress unoccupied most of the time, vandalism and unauthorised entry never stopped being a major problem. In fact the army conceded that damage due to vandalism had to be accepted. Not even steel doors proved a complete obstacle to the inquisitive and eventually the entrance doors were all bolstered.The steel shutters and doors remained favourite targets for vandals firing guns for many years.

Maintenance work to keep the hydraulic systems and engines operational to a minimal standard continued to be done until 1957. Earlier that year, the Police Department installed a radio station in the former BOP, and it was hoped that, in the short term, an added police presence would provide some security on weekends. In 1954 another Government department, the DSIR, briefly used the tunnels to conduct wind tests.

In 1955 the Post and Telegraph Department sought permission to use a small part the BOP for a VHF transmitter and aerial. Permission was also granted the following year to use the land occupied by the battery ordnance workshop, which was erected near No. 1 gun to service the installation of the guns in 1944. The workshop was later burned down, on 24 April 1957.However it was not until 1960 that the Post and Telegraph Department erected a new structure on top of the workshop’s concrete foundations. Later, after the army left Wrights Hill, the P&T Department became de facto occupiers of the entire complex. It concentrated its occupation of the underground area in war shelter 2 and magazine 2. In 1980, to guard against constant vandalism, these two areas were secured behind a 700mm reinforced concrete wall. Its successor, Telecom, stored equipment in war shelter 2 until 1997.

In common with the armies of Britain, Australia and Canada, New Zealand disbanded coast artillery as a branch of the service in 1957 and the 9.2-inch batteries were permanently shut. The threat to New Zealand’s shores was by then regarded as almost non-existent and in any case the batteries had been rendered technically obsolete by changing military technology. The Coast Artillery lingered on as the Coast Cadre, a branch of Army. Once the army left Wrights Hill the fortress attracted even more trespassers and vandals.

In late 1959 and early 1960 a Sydney company – Bradman & Co. – secured the contract to scrap the guns and much of the underground equipment at the 9.2-inch batteries, including Wrights Hill. This scrap was eventually sold to Japan, perhaps the ultimate irony. Later in 1961 the gunpits were filled in to prevent injury to the public. Meanwhile the Army continued to have to deal with the consequences of vandalism. It was suggested that an annual average of four days work was being spent ‘resealing openings and repairing doors.’

By 1962 the vast majority of coast artillery equipment in New Zealand had been disposed of. The 9.2-inch batteries were no exception and Wrights Hill passed entirely out of military use. The true cost of the 9.2-inch batteries will never be known, but it is likely to have been well in excess of £350,000 each. The construction costs are known; Wrights Hill cost £249,120 after an original estimate of £122,430, Whangaparaoa £241,138, original estimate £120,697, and Waiheke £286,285, original estimate of £124,740.

For 27 years the fortress was abandoned and unused except intermittently by Post and Telegraph staff, who also continued the process of stripping the fortress of those useful fittings that Bradman & Co. had left behind. By 1988, when the Karori Lions took the first steps in opening it up to the public were taken, the fortress was in poor condition. The complex was cleaned up over the following year, and on Anzac Day 1989, opened to the public for the first time. The enormous crowds that turned up on the day indicated what a high level of interest there was in coastal defence heritage and of course, confirmed the mysterious appeal of underground structures.

The Wrights Hill Fortress Restoration Society was inaugurated in 1992 and it began a programme of repair and restoration. Their presence and work dramatically reduced vandalism. In 1997, the WCC commissioned a conservation plan to guide work at the battery. Since then, restoration and maintenance – mostly of the internal spaces – has continued at the pace the volunteers can sustain. Open days are conducted five times a year (on public holidays and one day in December) and the fortress is regularly opened to interested groups, on request, at other times. Wrights Hill is sometimes used by TV and feature filmmakers.

-

-

close

Cultural Value

-

Significance Summary

close

- Wrights Hill Fortress is one of the country’s most important examples of coastal defence heritage, being one of just three 9.2 inch batteries built in New Zealand, the largest and costliest coastal defences ever constructed in the country.

- The batteries vividly illustrate the extent to which the Government, once motivated by world events, was prepared to go to defend the country.

- They remain a monument to the huge input of resources and human endeavour required to build them.

- Thanks to the care of the Wrights Hill Fortress Restoration Society, the fortress has had its decline arrested and many of its internal features restored. It is regularly visited by the public on open days.

- Aesthetic ValuecloseThe fortress is fundamentally a utilitarian design, with the various structures designed solely with their particular function and purpose in mind and without the slightest concern for the attractiveness of their appearance. Nevertheless there is an intrinsic aesthetic in many of the (predominantly) reinforced concrete structures, the vast majority of which retain the original exposed and raw finish of the concrete; this characteristic visual texture strongly accentuates their strong and uncompromising lines. Wrights Hill is a place that is well known in Wellington for its commanding views of the city, the various masts on its summit and its long association with the fortress. Thousands of people are aware of the heritage value of the fortress and the role it has played in the city’s heritage. Being a place constructed in a very short period of time (largely between 1942 and 1947) Wrights Hill is very much redolent of its World War II origins. And despite the significant changes that time, vandalism and scrapping have wrought, the fortress as a whole remains largely intact, a product of the fact that much of it is underground and built of reinforced concrete.

- Historic ValuecloseThe design and supervision of the construction of the batteries and their associated structures was the work of the Public Works Department. Despite the extraordinary demands on their time in a period of crisis, with critical work urgently required all over New Zealand, the PWD engineers and designers consistently provided innovative and intelligent solutions to the challenges presented by the time constraints, topography and constantly changing requirements from the Army. The construction of the Wrights Hill Fortress, including a significant amount of tunnelling to form the underground structures, was a massive undertaking that transformed the summit of Wrights Hill. Much of this work was done by the long-standing construction firm of Downers, which still operates today. The fortress stands as a tribute to the skills, resourcefulness and sheer hard work of the men who built it. The revival and restoration of Wrights Hill Fortress is due to the efforts of volunteers and in particular the work of the Wrights Hill Fortress Restoration Society. In time, their contribution will become increasingly more significant. Wrights Hill Fortress ultimately had a very brief history of military use. Even taking into account the period after World War II when it was kept on a ‘care and maintenance’ basis the fortress had a very short useful life. Yet the fortress has a representative and symbolic history that transcends the details of its abbreviated operation. World War II was an extraordinary time. It was arguably the pivotal event of the 20th century and there were few places in the world not affected by the titanic struggle between the Axis and the Allies. New Zealand was no exception. Allying itself to Britain and then the United States made New Zealand an enemy to Germany, Italy and Japan. It was the latter, with its interest in the Pacific and strong naval forces, which represented the greatest threat to the security of this country. By 1942, the Japanese military, moving southwards from Indonesia and the Phillipines was a real and deeply alarming threat to New Zealand. Against this backdrop, the building of Wrights Hill Fortress, and its sister installations at Waiheke Island and Whangaparaoa Peninsula, the biggest coastal-defence batteries ever built in New Zealand, can be seen as this country’s ultimate land-based response to the imminent Japanese threat. They were of course first planned some years previous, before hostilities began, but the building of these batteries was part of an extraordinary period of construction when hundreds of coastal defence installations, from massive forts like Wrights Hill, to tiny pillboxes on remote beaches were thrown up in a frenzy of activity all around the country. Conscious of the need to make the batteries secure and defendable, the government poured large amounts of money into the 9.2-inch installations. They were almost entirely underground, and such was the size and substance of these installations that they all remain intact, and basically in their structural entirety. Today they are remarkable monuments to a time when the world was in turmoil and New Zealand was anxious and isolated. The batteries can be seen as the ultimate culmination of 100 years of coastal defence in New Zealand; the last of their kind, they were rendered obsolete not long after they were finished by changing military technology.

- Scientific ValuecloseThe area has demonstrated its educational value via the open days held by the Wrights Hill Fortress Restoration Society since 1992. The fortress offers an opportunity for New Zealanders to see, in one place, the extent of efforts that were gone to protect the country from the threat of invasion during World War II. The 9.2-inch gun batteries were the biggest land based defensive batteries ever erected in this country and the guns and their emplacements were also the biggest ever of their kind in New Zealand. Although the emplacements are largely stripped of their equipment, they remain impressive physical structures all the same. The construction and arming of the battery, with so much of the work underground, in difficult terrain, represents a major engineering and technological achievement particularly when the difficulties posed by the urgent timeframe, ongoing design development, and the shortage of materials and manpower are taken into account.

- Social ValuecloseThrough the efforts of, firstly, the Lions Club and then the Wrights Hill Fortress Restoration Society the place has acquired considerable recognition and public esteem in the Wellington region.

- Level Of Cultural Heritage SignificancecloseThere are only three 9.2-inch batteries in existence in New Zealand. These kinds of batteries will never be built again and to that extent, they are unique. To the extent that it is meaningful, Wrights Hill is a good example of this kind of battery. It is notable amongst the other batteries for the surviving engine room equipment. The area retains much of its original fabric, particularly its core structure. Later additions or reconstruction have not undermined this value to any great extent. Is the area important for any of the above characteristics at a local, regional, national, or international level? National significance. Wrights Hill Heritage Area includes the underground and external remains of one of three huge 9.2-inch batteries built in New Zealand during the height of World War II. It is largely intact, retaining key machinery found at no other 9.2-inch site, and its size and manner of construction also add much to its technical importance. It remarins a well known local attraction.

- New Zealand Heritage Listclose{5A51C0D1-99D2-4277-8FAB-25C44DE9EFDE}

-

Significance Summary

close

-

close

New Zealand Heritage List

-

New Zealand Heritage List Details

close

Category 1

-

New Zealand Heritage List Details

close

-

close

Additional Information

-

Sources

close

Not available

-

Technical Documentation

close

Not available

-

Sources

close

Last updated: 1/12/2020 8:24:29 PM