Alexandra Road Chest Hospital

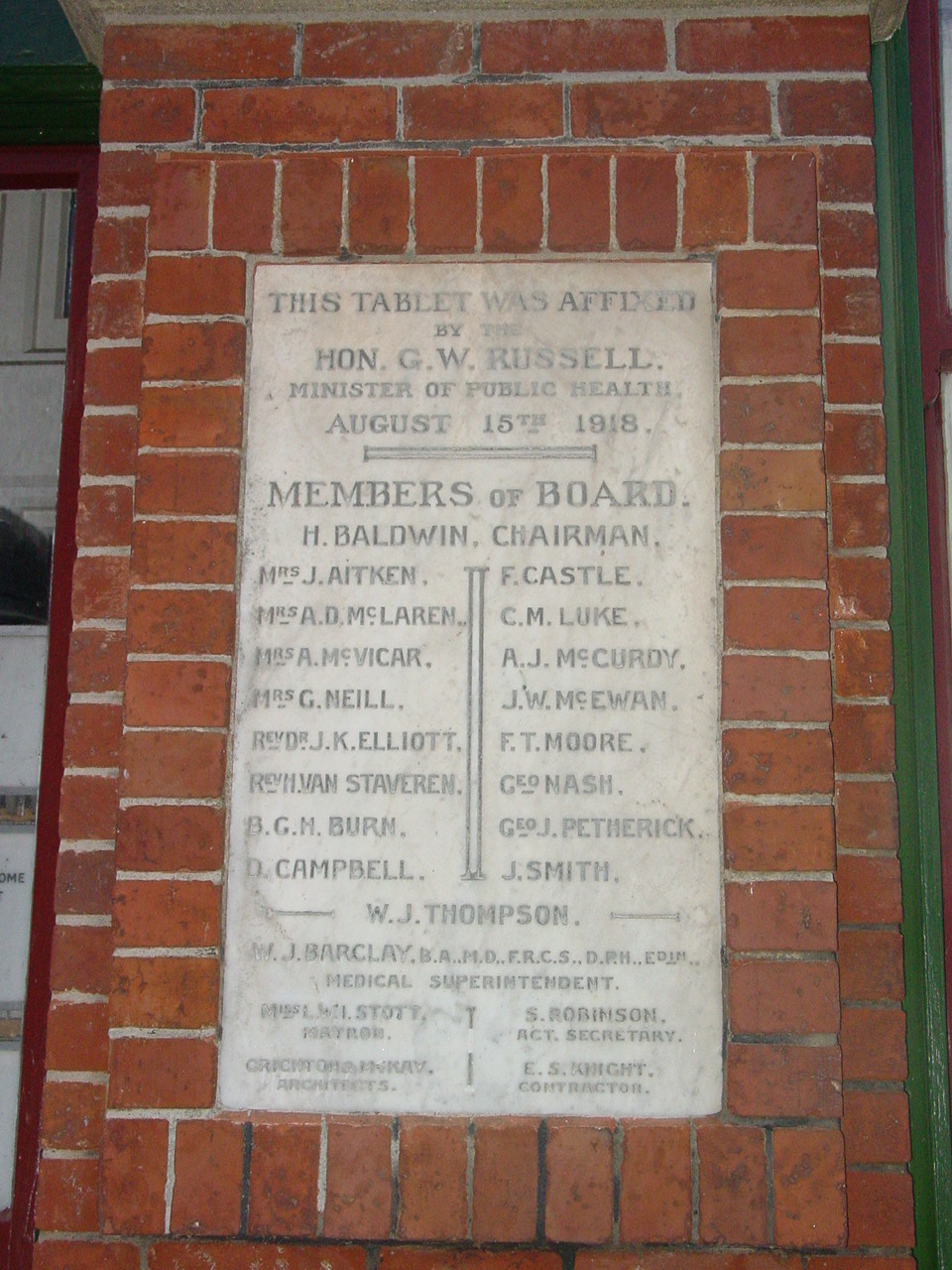

"This tablet was affixed by the Hon. G. W.Russell. Minister of Public Health. August 15th 1918

Members of Board. H. Baldwin, Chairman. Mrs J. Aitken, Mrs A. D. McLaren, Mrs A. McVicar, Rev. Dr. J. K. Elliott, Rev. M. Van Staveren, B.G.M. Burn, D.Campbell, F. Castle, C.M. Luke, A.J. McCurdy, J.W. McEwan, F.T. Moore, Geo. Nash, Geo. J. Petherick, J. Smith. W.J. Thompson

W.J. Barclay, B.A., M.D., F.R.C.S., D.P.H., Edin. Medical Superintendent

Miss L.W. I. Stott, Matron, S. Robinson, Act. Secretary, Crichton & McKay, Architects, E.S. Knight, Contractor "

Image: WCC, 2006

"Fever Hospital. Erected 1919"

Image: WCC, 2006

-

The Former Chest Hospital Heritage Area is one of the most important examples of an historic public health site in Wellington (and in New Zealand). It includes buildings that were purpose-built in the early 20th century to treat infectious diseases. Both the Chest Hospital Building and the former Nurse’s Home are included in the District Plan heritage area listing.

The land for the hospital was alienated from the Town Belt in 1872, although it was not put to hospital use until 1919, when the Fever Hospital was constructed. The Fever Hospital was an expansion of the hospital’s isolation facilities and capability (including the nearby Ewart Hospital [1910] at the end of Coromandel Street, and the Seddon Ward [1906] near the main hospital complex). Its remote site facilitated the isolation of particularly infectious patients and over its 60 year history it helped to manage outbreaks of disease and provide for the recuperation of patients.

The hospital was extended with a further wing in 1973, but within eight years it had closed. It had sporadic use thereafter until it entered a new phase in its history in 2014, when it became the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals’ new Wellington base.

-

close

Physical Description

-

Setting

close

The Former Chest Hospital Heritage Area is set high on the upper slopes of Mount Victoria, on a north-facing hillside site off Alexandra Road. When the Fever Hospital was constructed, the surrounding Town Belt land was almost entirely bare and the buildings were very prominent features in this landscape, standing out in views of Mount Victoria from Newtown to the city. However, over time the hillsides, and the Hospital, have been enfolded by trees – largely pine forest – and today the building is very difficult to view from any distance.

The site is flattish, with the land sloping down to the west, and rising up to the north; it is somewhat sheltered by the large knoll that overlooks Alexandra Park. The immediate surroundings are covered with growth; mature pohutukawa and other trees separate the buildings from Alexandra Road, and wrap around the south side of the complex; the knoll to the north is covered with regenerating scrub, and the most open outlook is to the west, over the Town Belt and across to Newtown and the city.

The driveway curves in to the site, rising gently from Alexandra Road, past the small pump house and below the south wing of the Hospital, leading to the forecourt; the Nurses Home is to the south side of the forecourt and the Hospital on the north; the two are linked by a covered way. A new extension to the driveway leads to a large parking area built over the former western lawn. A new single-storey building occupies the north-west corner of the site beyond the car park.

-

Streetscape or Landscape

close

-

Contents and Extent

close

The Former Chest Hospital Heritage Area, located on the west (city) side of Alexandra Road, occupies Lot 4 DP 316137. The area extends over the entire lot, and includes the whole of the Hospital building, interior and exterior, including the verandah, former Nurses’ Home, morgue, and other elements including the associated covered walkway. It also includes the small detached pump-house at the start of the driveway. The listing excludes the central wing (built in 1973), the caretaker’s wing, gas utilities building and attached shed, and the detached shed to the north of the Nurses’ Home.

-

Buildings

close

The original buildings comprise a coherent group of structures designed by Crichton & McKay and built at the same time in compatible styles and materials. They include the Fever Hospital itself, the adjacent Nurses Home and a small pump-house near the start of the driveway. It is presumed the reservoir on the nearby rise was put in place to service the Hospital, but this lies outside the heritage area.

Modern structures and alterations, put in place in 2013, were designed by BKB Architects of Wellington.

Fever Hospital

The Hospital is a large but predominantly single-storeyed structure, raised upon an undercroft structure above the various slopes of the site. The Hospital is designed in a domestic Queen Anne idiom; this style is also carried through to the Nurses Home and to the small pump house, making the complex a visually and stylistically coherent whole.

The hospital has a simple plan with a strong defining geometry - two major ward wings, subtending a 60° angle about a comparatively short central portion, containing administration and service areas; the modern short wing runs out between these to the south-west; the wings all have gable roof forms. The central axis is oriented north-east, setting one wing to a roughly northerly orientation and the other southerly. Each wing has small square semi-detached amenities blocks, rotated at 45° to the wings; one block for the northern wing and two blocks for the southern wing.

The modern wing (1973) is positioned centrally within the arms of the two original wings. The new ambulance garage, a single-storey rectangular box, is positioned by the south-east corner of the admin area and joined to it by a modest linking structure. A single-storey covered way links the Hospital to the Nurses Home; plant rooms and service facilities are arranged on the west side of this.

The design of the original Hospital is very carefully composed, with well-considered proportions and uses a sparse palette, both of materials and design features and forms, to great effect. From ground level at the main entry, the lower half of the walls are in neatly-worked brick with moulded coloured plasterwork accents, including bands at the floor level, sill level and a dado line at door head height; above this, the walls are finished in roughcast stucco, painted white. All of the external joinery is timber; the windows are particularly distinctive, consisting of unequal double-hung sashes, surmounted by a further top sash above the dado line. This basic distribution of materials, coupled with careful patterning and use of details, gives all of the original elevations a great visual richness and interest and creates a simple but attractive and obviously carefully-designed building.

The principal elevation is the south, to the administration block. This contains the main entrance porch, an enclosed structure denoted with a large brick-arched entryway brought forward of the main wall face, and has a pair of double doors with a semi-circular glazed overlight, all surmounted by a bracketed gable roof with half-timber infill at the eave; the marble foundation stones are set in the pilasters either side of the door. The part gable ends at either end of the admin block still contain the original diamond-shaped asbestos tiles.

The two original wings each have verandahs on two sides – fully glazed on the outside faces, and partly open on the courtyard faces; the verandah roofs are struck at the dado line, providing space for the windows above the roof to admit light into the rooms beyond, from both sides. Above these, the eaves are bracketed. The verandahs are timber-framed structures, with shallow-pitched roofs; the outside walls have spandrels clad in bevel-backed weatherboards and timber window joinery above. The courtyard side verandahs are intricately detailed, with elegantly carved verandah posts with arched screen timbers at the openings, multi-light timber joinery (a mixture of sliding and casement sashes) and a vertical shiplap weatherboard spandrel line.

Between these wings, the 1973 addition is a quite plain and dour single storey institutional building of its time, which sits well enough in the courtyard space, but which, in its palette of low-cost 1970s materials and standard hospital-board details, detracts from the fine visual quality of the original building.

Of the two wings, the higher elevation is the west one, along the length of the northernmost wing, where the undercroft is effectively a full storey in itself, and supports the building on a grid of large brick piers (the short wing to the south-west is two storeyed); at the courtyard between the wings, the ground is nearly at floor level, and it falls away again underneath the south wing, where the undercroft is half a storey or less. The large undercrofts are also used for reticulating building services.

The diagonally-set toilet blocks off the wings, raised to the eave height of the wings, have a distinctive arched undercroft; the toilet blocks are fully bricked, trimmed with a plaster band at the floor and ceiling levels, and are finished with a flat roof. These elements add an interesting visual counterpoint to the long run of the wings.

There are few obvious changes to the exterior faces of this building, which are largely in authentic condition – the most evident alterations are the unsightly heat pump installations at the northern ends, and the new ambulance garage (see below under ‘modern buildings’).

Nurses Home

This is a substantial two-storey masonry building, designed in the manner of a large domestic house in a Queen Anne idiom and matching the Hospital in most respects. Like the hospital, the design is carefully composed and designed, with well-considered proportions using a similar sparse palette of materials and design features and forms.

The plan is rectangular with the main elevation and main entry porch to the north side. There is a single-storey extension to the west of the porch, covered with a hipped roof. The roof is complex, with two parallel gabled roofs running east-west with an internal gutter between, giving two gables on the west elevation and one on the west, and a major gable running at right angles to the main roof on the south-east corner, facing south, and there are two prominent chimney stacks in brick. Each gable has decorative half-timber work, and the eaves feature decorative bracketing.

The lower storey is in brick with prominent plaster heads and sills to the windows; the upper storey is finished in light-painted stucco, with a dentil course in the gable ends. All the external joinery is timber. The main elevation faces north and contains the main entry, covered by a mono-slope porch roof, which marries in to the covered entrance to the Hospital. This is surmounted by a flat-roofed timber-framed sun porch, clad in bevel-back weatherboards and finished with an impressive array of 15-light sliding windows and a fire-escape door at the western end. The building’s windows are typically double-hung, in unequal double-hung sashes of six over nine lights. There are two side entrances each accessed up a neatly plastered flight of steps, each covered with a bracketed porch roof, and each with a handsome set of entry joinery, consisting of a large glazed door surrounded by side-lights and over-lights, - one on the west (signed ‘Guest Entrance’) and one on the east.

-

Structures and Features

close

Pump House

The pump-house is a small stand-alone building near the east end of the driveway. Built in the same style and from the same period as the other buildings, it has white roughcast walls and a hipped corrugated steel roof; an arched doorway faces the driveway. It is outwardly intact.

Modern buildings

The modern garage is a plain rectangular single-storey box with a flat roof, positioned to the east side of the administration block. It unfortunately serves to block views of the south wing and disrupts the elegant original composition of the whole forecourt area, detracting from the appearance and visual quality of the original buildings.

The separate service building at the north-west corner of the site is similarly single-storeyed, but is positioned not to detract from the original buildings.

The service buildings to the west side of the covered way are generally newer than the original hospital buildings, and are, in the main, featureless rectangular boxes. The covered entranceway masks them from the forecourt side, although they stand out somewhat when seen from the west.

-

Other Features

close

Other features include the low random-rubble retaining walls along the driveway and mature trees and vegetation. As part of the 2013 redevelopment of the site, the area now includes a new garage at the top of the driveway attached to the south wing, a long extension on the driveway leading to a car-park on the former western lawn, and a new standalone amenities building at the north end of the site.

-

Setting

close

-

close

Historic Context

-

The Former Chest Hospital Heritage Area is located on land that was originally reserved for the Wellington Town Belt. The Town Belt was provided for during the process of surveying and laying out the city in 1839. These wooded areas that would become the Town Belt had already been in use for many years by Maori prior to this. Ngai Tara had built a series of pa throughout the woods, with the largest being the Akatarewa Pa near to Wellington College and extending up the ridgeline. The Basin Reserve, then a great swamp, was known as Hauwai and was a mahinga kai for the pa.

In 1839, New Zealand Company surveyor Captain William Mein Smith was instructed to lay out the settlement of Wellington. Part of his brief included the instruction that ‘…the whole of the town inland should be separated by a broad belt of land […] to be public property on condition that no building ever erected on it’. By August 1840, the plans for the city in its final position were completed with the belt of land denoted ‘…land reserved for the enjoyment of the public’. This plan is the first formal record of the Town Belt.

In 1841 the Port Nicholson Deed of Purchase, under which land for Wellington had been obtained from Maori, was made invalid and became the subject of a later inquiry and redress. The Crown assumed ownership of the Town Belt areas (approximately 625 hectares at this time) and proclaimed the land as public reserve, without compensation. Governor Hobson published a notice in the New Zealand Gazette that required anyone occupying the public or native reserves to vacate those areas.

From the late 1840s until the 1870s one third of the originally-surveyed Town Belt was taken for various purposes including; native reserves, which were awarded to Maori in partial compensation for land taken by the Crown, for social welfare and education purposes, and for public works. Some land was also sold for residential development or was claimed for roads. In 1873 the remaining land that was designated as the Town Belt was transferred from the Crown to the City of Wellington by the Wellington City Reserves Act 1871 and Basin Reserve Deed 1873.

The 1873 Town Belt Deed set the terms by which the city (as Trustee) was to administer the land. As the city continued to grow, parts of the Town Belt were developed and managed for recreation and public amenity purposes, including for public health.

In 1872 part of the town belt land near Riddiford Street was appropriated for the construction of a lunatic asylum and a general hospital and in 1877, under the Wellington City Reserves Act Amendment, a further eight hectares of the land was conveyed to the trustees of Wellington Hospital. In 1908 the Mental Health Reserves Act transferred further land to the hospital.

Early development of Wellington Hospital

The first hospital in Wellington was the Colonial Hospital, built in 1847 at Pipitea Street on land gifted by Maori for that use. This was a two-storey masonry structure that stood on the present site of Wellington Girls’ College. The building was significantly damaged in the 1848 earthquake, although it was soon repaired and kept in service for a few more years.

Planning started for a replacement hospital in 1851, a single-storey timber structure holding 40 beds, which was eventually opened in 1855 on the same site. By 1870 this building was beginning to run out of capacity to meet the requirements of the growing settlement and sanitary conditions had deteriorated.

Planning began for a new, much larger hospital, designed around the new understandings about hygiene derived from Scottish surgeon Joseph Lister’s landmark work in antiseptic surgery in the late 19th century. Some four hectares of land was set aside in Newtown, with room for expansion on a largely flat site. Further land was appropriated from the Town Belt in the following years. The hospital was finally opened in 1881. It was repeatedly added to over time, with major new wards opened in 1888 and 1894, and a new operating theatre in 1901.

A standalone Nurses’ Home was built in 1904. An enormous four-storey brick Victorian Gothic structure, it was located on the side of the hill just to the north of the main hospital. In 1905 the Victoria Hospital for the Chronically Incurable, a large two-storey brick building, was opened on the hill to the south-east.

Infectious diseases, isolation wards and the Fever Hospital

In 1892, the ‘Hill Ward ‘was quickly built near the main hospital to help deal with an outbreak of typhoid fever. The concept of isolation was well understood by medical professionals by this time and the building of separate hospitals evidences growing understanding of the ways in which the spread of infectious diseases could be combated and of the most effective ways to treat the victims.

In 1903 the Government placed the responsibility for dealing with infectious diseases, such as scarlet fever, measles, chicken pox and influenza, directly with local hospital boards; this soon led to the construction of purpose-built isolation facilities throughout New Zealand. In Wellington, the first response was to build new isolation wards. In 1906 the Seddon Ward and shelters, for tuberculosis patients, were opened. These sat on the hillside to the east of the main hospital.

The Hospital Board then set out to build a new Fever Hospital, to augment these isolation wards and provide treatment separate from the main hospital. This first Fever Hospital, later renamed the Ewart Hospital, was opened in 1910, on a site at the end of Coromandel Street. This was a large two-storied complex, with two wings canted symmetrically about a central entrance, and had its own Nurses Home and administration block. This building was later added to 1919, as a response to the inadequacies of the older Seddon Ward and shelters.

The Ewart Hospital was not able to cope with any sharp rises in cases of infectious disease. It was proposed that a dedicated scarlet fever ward be constructed so that the cases could be more effectively and efficiently monitored, and that Ewart be converted to a dedicated diphtheria ward.

The site for the dedicated scarlet fever building was on land taken from the Town Belt, and described as the Board property at the ‘top of the hill’. Council documents of the time give the location as Constable Street, but the site was a significant distance from Constable Street and there was no road access from there to the proposed site. As with the Ewart Hospital, the new Fever Hospital had its own Nurse’s Home and offices on site.

The new buildings were designed by prominent local architects Crichton and McKay, who had by this time already won several commissions from the Wellington Hospital Board. The chosen site was away from the main hospital and the city in order to prevent the spread of diseases. The concept of isolation was well understood by this time and the building of separate hospitals is evidence for the growing understanding of the ways in which diseases could be fought.

[Insert plan of various hospitals – Seddon ward and isolation units, Ewart Hospital and Fever Hospital]

The construction of the Chest Hospital

In August 1917 engineers Seaton, Sladden & Patrick began constructing access and levels for the new hospital site. The building permit was issued in February 1918, and tenders for the building were called. The tender of E. S. Knight for £25,500 was accepted and construction began. The foundation stone was laid in August 1918. Progress was slow, probably due to the difficult access to the site; there was no formed road to the hospital until the 1930s. Access was presumably gained from Ewart Hospital below. In February 1919 tenders opened for ‘a track from old to new Fever Hospital’ and the cheapest tender, of Lynch & Burke, was accepted. The hospital was occupied in January 1920 although it appears to have had no formal opening ceremony.

A note made in 1917 on the recommended procedures for treating scarlet fever gives a clue as to the reasons for the character of the hospital design, with its large open spaces and open verandahs; ‘A top floor excellent, large, airy, well lighted and with a fireplace, ready access to bathroom and to room set apart for attendant…prepared by being stripped of all pictures, hangings, ornaments, rugs, carpets, and surplus furniture’.

The new Fever Hospital provided additional capacity to the Ewart Hospital and does not appear to have been exclusively used for the treatment of scarlet fever. It was first used to house ill servicemen returning from World War I. At the same time the hospital housed patients suffering from scarlet fever, measles, influenza, and chicken pox; it later housed patients suffering from other epidemics including polio.A report dated 25 May 1922 on ‘Infection in Hospital’ gives a good indication of how the hospital ran the day to day isolation of infectious disease: ‘Scarlet Fever, Influenza, Measles, and Chicken Pox cases in the Fever Hospital are held in separate wards and their linen and food utensils kept separate’.

Use and change

In 1933 the Fever Hospital was forced to temporarily close for repairs. A report by local architects and engineers, King & Dawson, identified leaks caused by problems with the asbestos roofing (presumed to be diamond-pattern ‘slates’), and recommended re-roofing the buildings with felt and heavily galvanised corrugated steel. The corridor and verandah roofs were repaired with ‘patent fabric roofing – Malthoid’ and new gutters.The repairs were completed by 1935.

The 1940s saw a new epidemic – tuberculosis – quickly become the principal threat to community health. Large numbers of tuberculosis cases on top of other infectious diseases began to stretch the hospital. One measure undertaken to accommodate all the cases that were starting to accumulate was to house the tuberculosis patients out on the verandahs. Tuberculosis was seen as a ‘grave threat to the community’ but according to hospital staff from the time the stringent isolation procedures that had been previously put in place for other fever patients, with great success, were not adhered to. Sonia Davies worked at the hospital as a nurse during World War II, and like many in her class (11 of 36) contracted tuberculosis. It would appear that precautions for nurses at the time were minimal; the superintendent is reported to have said that if he were to invalid all nurses who presented with a shadow on the lung he would have no staff.

With the advent of antibiotics and effective vaccinations giving rise to great improvements in public health after the World War II, demand for isolation facilities for infectious diseases quickly began to fall off.

Following World War II the Fever Hospital began to fall into disrepair, presumably through a lack of maintenance given the otherwise good quality of the buildings. Alternative accommodation for the patients was investigated and quotes for repair work and alterations were received. No work was actually carried out. In the same period, treatments for several infectious diseases greatly improved, and the demand for the facility slowly decreased. By 1953 the hospital only had four patients, each isolated in their own rooms. The following year it was closed. Some minor renovations were carried out at this time to the lighting and new linoleum was laid. In 1957 the hospital was temporarily re-opened to house tuberculosis patients sent up from Ewart Hospital.

A new Seddon Wing, a modern seven-storey reinforced concrete structure, was opened in 1966 on the main hospital site, replacing the old Seddon Hospital building. However, by the time it opened, tuberculosis rates had significantly decreased, and the new building was instead put to general use, housing medical wards.

In 1969, proposals were floated to reuse the Fever Hospital as an isolation unit, and a full inspection was carried out, followed by considerable upgrading of the hospital building and facilities and in February of 1971 patients from the Ewart hospital were transferred to this ‘Temporary Fever Hospital’. With the anticipated closure and demolition of the Ewart Hospital, both further upgrading and the construction of an additional new ward was required, the latter being built between the two wings of the existing building. The extra ward was completed in 1973. By the late 1970s one ward was separated for the continuing care of elderly patients.

Closure and an uncertain future

In 1977, a site and facilities analysis was carried out that indicated that the building’s functions had to move to a new site. In 1981 the poor condition of the hospital and the low number of patients led to it closing again. Upon the closure of the hospital the Wellington City Council carried out investigations into the status of the title and the land. However, it was still some time before the land was returned to the Council.

In 1987 the hospital buildings were taken over by the Wellington Polytechnic as the new home of the School of Music. The buildings were by this time in quite poor condition and some internal refurbishment and adaptation was carried out to make them fit for occupation. The grounds were used to support horticulture and landscape design courses. The Wellington Polytechnic School of Music stayed in the building until 1998.

Assessments carried out in 1998 identified the buildings’ high heritage values, and WCC made a decision to find a new purpose for the buildings to keep them in use. However, by the early 2000s the buildings had yet to find a permanent occupant and were empty for the majority of the time. In the meantime, because the hospital use had ended, the land – including the buildings – was returned to the Wellington City Council in 2002.

In 2004 Wellington City Council issued a request for proposals for the future use of the buildings as, in their unused state, they were falling into disrepair and attracting vandalism. The preferred proposal was submitted by the Wellington SPCA and in 2005 the Council and SPCA entered into a lease agreement. The SPCA by this time had been looking for new premises for over a decade, as its Newtown facility, near Wellington Zoo, was too small to meet its requirements and the site had no room for expansion. WCC considered that the reuse of the building as an animal hospital and shelter fitted well with the previous use of the building. However, the SPCA project soon stalled due to concern over the magnitude of the works that were needed and internal disagreements. Over the next few years, as they stood unoccupied, the buildings continued to deteriorate and be vandalised.

A change of management at the SPCA in 2011 led to a reconfirmation of the partnership between the Wellington SPCA and Wellington City Council in 2012. The Council worked to structurally upgrade the buildings and repair the exteriors (the buildings had in the meantime been assessed as earthquake prone in 2009), while the SPCA was responsible for the interior restoration and refurbishment of the Hospital. The SPCA also modified access to, and greatly expanded parking at, the Fever Hospital and constructed several new buildings including an ambulance bay and new animal wings. After the substantial works to the exterior and interior of the building were completed, the building reopened as new home of the Wellington SPCA on 6 February 2014.

At the time of writing, the Nurses Home was scheduled for upgrading work – with some repair work completed – and intended to be occupied by the SPCA in 2015 or later.

-

-

close

Cultural Value

-

Significance Summary

close

- As a purpose-built facility, designed to the best principles of public health care of the day, the Former Chest Hospital represents a significant physical waypoint on the continuum of evolving treatment of infectious diseases. This also gives the complex high technological value.

- The complex is very rare, being one of only two examples of its kind surviving in New Zealand (the other is in Dunedin). The buildings have been little modified over time.

- The complex has very high architectural and aesthetic value, with the Chest Hospital, Nurses Home and a small pump house comprising a coherent and attractive group in an interesting and visually rich Queen Anne idiom.

- The architects were Crichton & McKay of Wellington, a successful partnership that did much work for Wellington Hospital and helped establish its early 20th century appearance.

- Aesthetic ValuecloseThe Former Chest Hospital Heritage Area has high aesthetic value as a collection of cohesive buildings and open space that is rarely found in an urban environment. The design, by well known architects Crichton and McKay is a handsome antipodean version of the Queen Anne style (and influenced by Arts and Crafts philosophy). Both the Hospital and the Nurses Home are simple, attractive, well proportioned buildings that both retain a significant amount of original materials. The Fever Hospital was once a prominent landmark on the bare shoulders of Mount Victoria; however, as time has passed, trees have grown to mask it from wider view. Within the complex itself, the design and layout of the buildings about the courtyard, and within the constraints of the site, creates a distinctive local landmark, with a high level of visual interest. The heritage area contains a particularly cohesive collection of old buildings, the work of well-known and respected Wellington architects Crichton & McKay, carefully designed in a Queen Anne idiom, harmoniously scaled and made with a matching palette of materials, to great visual effect. The old buildings are well made with good materials and a high level of original craftsmanship is evident. They retained a hospital use for over 60 years.

- Historic ValuecloseThe Fever Hospital is intimately associated with the development of Wellington Hospital, most particularly the development of isolation facilities, which started in the late 19th century. The hospital can be regarded as one of the most important public organisations in Wellington. The entire complex is a very rare example of old buildings surviving from the early era of development at the Riddiford Street hospital site. The Former Chest Hospital Heritage Area is intimately associated with the progress of public healthcare in New Zealand. It was designed specifically to accommodate patients suffering from the infectious diseases that were a major public risk at the time. This type of bespoke building, designed specifically for the effective isolation of groups of patients, eventually became redundant due to advances in medicine reducing the incidence and severity of most of the diseases. It nevertheless remains an important waypoint in the history of hospitals and public medicine in New Zealand.

- Scientific ValuecloseThe heritage area is of very high educational value as it demonstrates a now very rare example of the development of medical practice in New Zealand and in particular progress in the treatment of infectious disease in the early years of the 20th century. The complex represents an important point along the continuum of infectious disease treatment. This quality is enhanced by part of the complex being accessible to the public. The heritage area contributes significantly to our understanding of New Zealand medical history. The former Fever Hospital is of technical value as an example of an early twentieth century hospital building. It retains a number of features and original material from the time of its construction, along with a high level of detailing and craftsmanship that make the building stand out as special.

- Social ValuecloseThe area, although remote from the urban area and rather secluded, is surprisingly well known to the public. This level of public knowledge will be broadened over time with the SPCA’s use of the buildings.

- Level Of Cultural Heritage SignificancecloseThe Fever Hospital building was designed specifically in response to the health concepts of the time and demand for managing infectious diseases like scarlet fever and tuberculosis, and is one of only one of two purpose-built infectious disease hospital buildings remaining in New Zealand (the other being Pelichet Bay Infectious Diseases Hospital, Dunedin). The area is an especially good example of its kind, being clearly built for its purpose and to the best standards of the time. The area, despite recent modifications, has extremely high levels of integrity and authenticity. The complex was never greatly modified during its working life for the hospital, and the buildings remain in largely original condition, particularly on the exterior. Is the area important for any of the above characteristics at a local, regional, national, or international level? Nationally important. The Former Chest Hospital is one of just two examples of a purpose-built fever hospital from the early 20th century still standing in New Zealand. Comprising a collection of largely unmodified, handsome brick buildings in a Queen Anne style, the hospital is one of Wellington’s most significant Edwardian public buildings.

- New Zealand Heritage Listclose{5A51C0D1-99D2-4277-8FAB-25C44DE9EFDE}

-

Significance Summary

close

-

close

New Zealand Heritage List

-

New Zealand Heritage List Details

close

Category 2

-

New Zealand Heritage List Details

close

-

close

Additional Information

-

Sources

close

Not available

-

Technical Documentation

close

Not available

-

Sources

close

Last updated: 1/13/2020 1:01:08 AM